the golden gate bridge

For almost 70 years, the Golden Gate Bridge has been a frequent site for suicide. While the Bridge District has failed to take the action needed to stop these deaths, research and studies within the medical community have deepened our understanding of suicide and how to prevent it. As the science of understanding suicide now stands, we can say without a doubt that preventing the possibility of jumping from the Golden Gate Bridge will save lives. There are three principal reasons for this:

-

1. Research has consistently shown that if access to a single means of suicide is restricted, overall suicides decrease.

-

2.Suicide is often an impulsive act, and lives are saved when a suicidal person gets past the impulse.

-

3.We have direct evidence that lives can be saved at the Golden Gate Bridge.

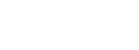

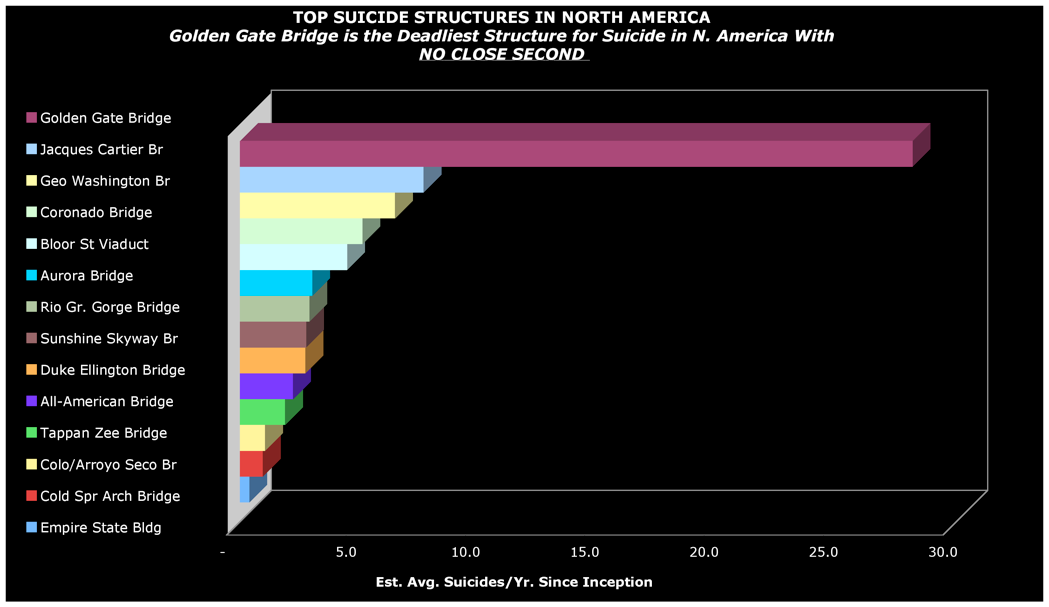

The Deadliest Structure on Earth For Suicide

Statistics

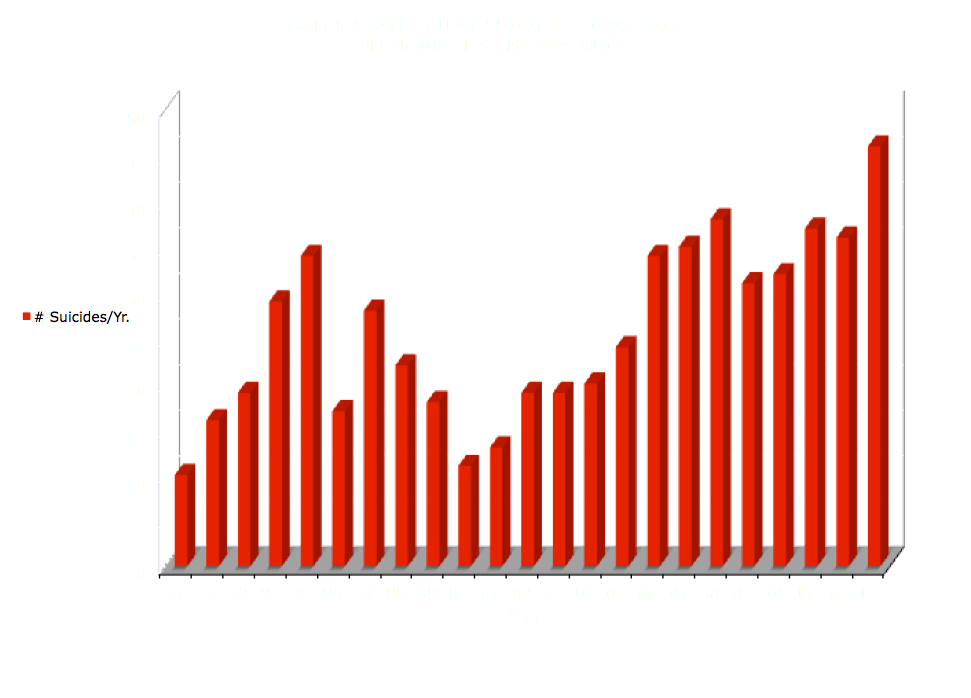

Note: Statistics are as of YE 2010.

Demographics

The Marin County Coroner did a study in July, 2007 about the demographics of those who ended their lives from the Golden Gate Bridge over a 10 year period. Contrary to popular opinion that tends to label all jumpers as psychotic schizophrenics, the victims came from all walks of life. While some suffered from mental illness, many more were overcome by a temporary impulse, chosing a permanent solution to a temporary problem.

Click below to see study:

Download the release

Download the charts

Media

New York Times Sunday Magazine, "The Urge to End It All", July, 2008

A comprehensive discussion of suicide, impulsiveness and current research.

San Francisco Chronicle, "Lethal Beauty Series", November, 2005

The San Francisco Chronicle published a multi-part series on the bridge suicide problem.

The New Yorker, "Fatal Grandeur of Golden Gate Bridge", October, 2003

The New Yorker published Tad Friend's essay on the bridge and its suicide history. This article is widely credited with inspiring much of the current effort to build the barrier.

The Bridge, 2006

A documentary by Eric Steele that follows a full year on the Golden Gate Bridge and records a number of suicides, with interviews of friends and family of those who jumped.

Click here for more information.

The Joy of Life, 2005

Jenni Olson's 2005 film is an experimental exploration of two themes : Suicide on the Golden Gate Bridge, and a young lesbian's search for love and self. Available at Blockbuster Online and NetFlix.

Click here for more information.

The Washington Post, “Golden Gate: A Bridge Too Deadly”, March, 2008

After longtime resistance, Bay Area may follow other efforts to prevent suicides at landmarks

By Karl Vick, Washington Post Staff Writer

The day Ken Baldwin decided to kill himself, he drove past his office and proceeded directly to the Golden Gate Bridge. Gazing at the Pacific Ocean over a railing only four feet high, he found the sole remaining impediment to his death was his own willpower, which turned out to be fleeting. "I counted to 10, and I couldn't do it," Baldwin said. "And I counted to 10 again, and I vaulted over. "And my hands were the last thing to leave, and once they left, I thought: 'This is the worst decision I've ever made in my life.' "

By surviving the leap, Baldwin defied the odds: Of the more than 1,300 people who have leapt from the Golden Gate, 98 percent have indeed perished. But in living to tell the tale, Baldwin also upended the stubborn assumptions that have kept the bridge's railings so easy to climb over, and have maintained the magnificent structure's status as by far the most lethal suicide site in America, if not the world.

The assumptions -- including the deeply held but incorrect belief that the suicidal are determined to die -- are as stubborn as the boutique agency that governs the Golden Gate. Last year, at least 37 people died after jumping from the bridge, a suicide every 10 days. Yet for seven decades, the Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District has pushed aside evidence that prompted the construction of effective barriers on other bridges and landmarks, including the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Aurora Bridge in Seattle, the Bloor Street Viaduct in Toronto, the District's Duke Ellington Bridge and, most recently, the Cold Spring Canyon Bridge outside Santa Barbara, Calif There, the state transportation agency that controls every bridge in California except the Golden Gate is hastening to install a barrier on a span with 1,250 fewer fatalities. CalTrans officials point to a University of California survey's finding that nine out of 10 people prevented from jumping off the Golden Gate were still alive years later or had died of natural causes, despite the rationale that a barrier would prompt them only to "go somewhere else to end it."

The study is part of a growing body of scientific literature that explodes persistent myths about suicide while reinforcing a simple principle: When it is harder to kill oneself, fewer people do so. The findings, some of which date back a quarter-century, have yet to persuade the bridge district, which is governed by a board of 19 people appointed from the nine counties that floated the bonds to build the Golden Gate 71 years ago. The first public plea for a higher railing came just 18 months later, from the California Highway Patrol.

"Where suicide is concerned, misdirection and delay have been the modus operandi of the bridge district for years and years," said David Hull, whose daughter Kathy leapt from the Golden Gate five years ago. Hull heads the Bridge Rail Foundation, an advocacy group formed by grieving parents, mental health advocates and the coroner from Marin County, which sits on the side of the bridge where most of the bodies wash up. Under the weight of the scientific evidence, media reports and lobbying by groups such as Hull's, the bridge district is seriously considering a variety of possible barriers, including a net. "If you took a vote today, it could go either way," said J. Dietrich Stroeh, a board member who has opposed the railing.

Opponents of a fence are wary of altering the appearance of an iconic structure that many local residents refer to as "my bridge." But their reluctance challenges San Francisco's progressive reputation. The bridge district this year found $25 million to install a movable median to divide two-way traffic on the bridge, where a total of five head-on collisions have claimed a single life since 1997.

The cost is at the upper end of estimates for erecting a barrier to prevent the kind of leaps that killed more than 200 in the same period. Advocates say the board's resistance reflects a widely held and deeply seated repugnance of suicide. "Probably so," Stroeh said. "It's a sad commentary on humanity, but it's considered a weakness. I think that's changing." The change coincided with a flurry of mortifying publicity. The bridge rail returned to the board's agenda after the 2006 release of the documentary "The Bridge." Stirred by a New Yorker article published three years earlier titled "The Fatal Grandeur of the Golden Gate Bridge," filmmaker Eric Steel stationed camera crews on either end of the span for a year, training lenses on the walkways. The film shows more than a dozen people tumbling toward the water as the camera lurches to keep the falling body in frame. "Makes you face it," Stroeh said.

On Aug. 20, 1985, Baldwin had the Golden Gate firmly in mind. "It was a long drive. I was thinking a lot," he said in a telephone interview from Angel's Camp, Calif., where Baldwin tells the story each October to students in the mechanical drafting classes he teaches at the local high school. "The closer I got to the bridge, the happier I got, because all this was going to be over. And one of the weird things I thought about was, the day after I jumped people would go: 'All right, a new day. We'll go on with our lives.' There would be no pain, no loss, no suffering. "It's a brutal thing to think of yourself as so minuscule in people's lives." He parked in the public lot on the San Francisco side, walked onto the bridge and peered down at the rocks. "I didn't want to have to be a mess. I wanted it to be a clean break. I just wanted to go away. "I got to the middle of the bridge, and I started going, 'Can I do this? Am I strong enough to do this?' "I started looking around. I didn't want anybody to touch me. I didn't want anybody to be aware of me. This was a bona fide attempt."

Two years earlier, gripped by the depression that left him feeling worthless and inept, especially at work, he had attempted suicide using pills and alcohol. Now he twice counted to 10, leapt the low rail and thought: " 'I can't believe that my life made this turn, so I have to do this.' "I was just flabbergasted," Baldwin said, "that this is where it took me, and this is where it was all going to end." The most stubborn belief against a barrier is that it would be pointless because people intent on ending their lives would find somewhere else to do it. "They think we're a bunch of goofballs," said Kevin Hines, who leapt from the Golden Gate in September 2000, immediately regretted doing so, and frantically swung his body in the four seconds it took to travel 25 stories. He entered feet-first. Fished from San Francisco Bay by the Coast Guard cutter on constant standby below the bridge, Hines emerged from a coma after 40 days. He now serves on the San Francisco Mental Health Board. "They say, like, if people want to kill themselves, they're just going to do it anyway," he said. The assembled evidence indicates otherwise.

Experts point first to Britain, where for decades the coal gas piped into homes for heat proved an extraordinarily handy method for self-destruction. "A little suicide parlor in the home," said Richard Seiden, a retired psychology professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Yet when utilities replaced coal gas with less-toxic natural gas, the national suicide rate plummeted. "They didn't go out and get knives," Seiden said. Advocates note that British authorities reached past the taboos that swirl about suicide to address it as a public health issue. Understanding that reducing "easy access to lethal means" translates into saved lives, the Brits stopped the sale of non-steroidal painkillers in bulk, making the pills available only in blister packs. "To get a lethal dose of ibuprofen, you get a very sore thumb," said Eve R. Meyer, executive director of San Francisco Suicide Prevention. The volunteer organization, the oldest in the country, trains staff members and volunteers answering suicide hotlines to "go after the weapon," Meyer said. "First, you try to find out how they want to kill themselves: Get it unloaded, untied, rolled across the floor. Distance is time, and time is your friend."

The notion at the heart of the training -- that even the most elaborately planned suicide is essentially impulsive -- was illustrated most persuasively by Seiden's 1973 survey, "Where Are They Now?," published in the journal Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. The researcher set out to learn the fate of 515 people who came to the Golden Gate to die but were prevented, either by passersby or by the patrols that roam the bridge looking for likely jumpers. Using public records spanning decades, Seiden determined that 94 percent were alive or had died of natural causes. "That's the whole rationale for suicide prevention: that it is crisis-oriented, that there's an episode of vulnerability and you get them through it," Seiden said. "If you had to follow them around the rest of their lives with a butterfly net, it wouldn't work. But by and large, you don't." Seiden's finding has been reinforced by reports from a variety of cities -- Toronto; Augusta, Maine -- where new barriers prevented jumps from the local "suicide bridge" without sending the fatal traffic to new sites.

Researchers frequently point out that the barriers erected on the Ellington Bridge over Rock Creek in 1986 produced no rise in suicides from the Taft Bridge, just a block away. "It's not that people chose an alternative method," said Andrew R. Pelletier, an epidemiologist for the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "They just didn't commit suicide once the method wasn't available." His life flashed before his eyes, Baldwin said, but it was not his past: "It was my daughter. It was my dog. It was my wife. It was my family, mom, dad, brothers. And I thought: This is horrendous. They're going to be devastated. "And I was going down at the time. The one time I clearly understood the consequences of what I was doing, it was too late. I just went, 'Oh. I'm an idiot.' "And from here on out, things get blurry.

"I looked down at the water, and it's rushing up at me, and I black out. I don't remember anything more about the fall itself. I don't remember hitting the water. The next thing I do remember is I'm swimming and I'm thinking, 'Someone, please, help me. I want to live.' " The next thing Baldwin knew, he was on a Coast Guard cutter and people were cutting away his clothes. "They were saying, 'Do you know who you are?' 'Do you know what you did?' 'Do you know why you did it?' 'Do you have a phone number?' "One of them said: 'Do you want to do that again?' "And I remember chuckling. 'No. Not really.' "